Joshua Browder

Building a $250M AI Lawyer, Hacking a $1B Restaurant, and Interviewing Warren Buffett

Joshua Browder is the Founder and CEO of DoNotPay, known as “The Robin Hood of the Internet.” He launched DoNotPay as a teenager and, as a Thiel Fellow, has raised millions from investors including Coatue, Founders Fund and Andreessen Horowitz automating hundreds of legal and consumer rights processes.

Alongside leading DoNotPay, Browder is a solo GP at Browder Capital, his venture fund.

His father was the number one enemy of Putin.

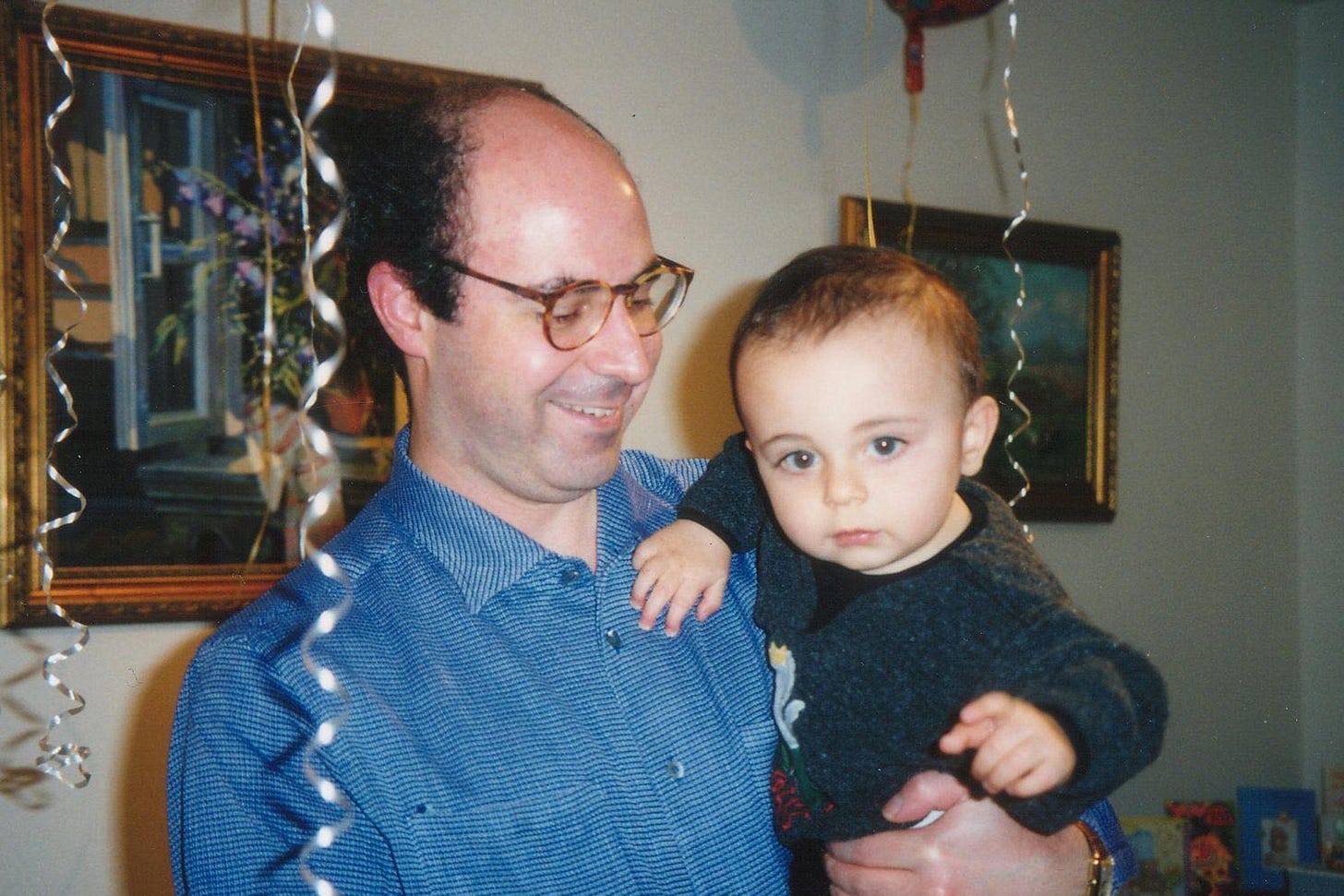

Joshua Browder grew up in a house under siege. In the Hendon district of northwest London, where the 2000s unfolded in a steady, metropolitan rhythm, his family’s life was anything but ordinary. His father, Bill Browder, was a political activist who had become what his son would later call “the number one enemy of Putin,” a man responsible for freezing the Russian president’s money around the world. This was not an abstract political battle fought in headlines; it was a war that came to their door. There were visits from the Russian mafia, a constant barrage of “really scary phone calls,” and a paranoid awareness that settled over the family like a London fog.

This inheritance of paranoia was at odds with the burgeoning digital world of a boy born in 1997. While his father saw danger in every connection, Joshua wanted to build an online presence, to make internet friends, to rebel against the family’s enforced isolation. Yet, the crucible of his upbringing forged a unique perspective. The ups and downs of building a company, the feeling of “eating glass sometimes,” would always be secondary; he knew early that “nothing compares to having dangerous people after your family.” From his parents, he absorbed two distinct, powerful lessons. Though they were not technical people, they taught him to “fight for what you believe in.” His father fought regimes; his mother, the daughter of a woman who fled the Nazis, fought waste. He remembers his grandmother taking salt packets from restaurants, a habit of scarcity she couldn't shake. This ingrained frugality became his own. “My company is called Do Not Pay,” he would later reflect, “it’s not just a company, it’s a lifestyle.”

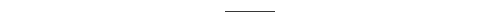

Josh struggled in school, navigating the frustrating landscapes of dyslexia and dyspraxia. He felt like a failure in English class, a world of abstract words that wouldn’t bend to his will. He had to push himself to find something he was passionate about, an outlet where the rules made sense. Sure enough he found it, at age twelve, not in a classroom, but in the flickering light of YouTube videos. He taught himself to code, watching Stanford iOS development tutorials from an ocean away. Code was his rebellion and his salvation—a logical system that gave a young person leverage, a way to build something without asking anyone’s permission.

Sued for hacking into a major restaurant chain.

Armed with his self-taught coding skills, he looked at the world around him and saw gaps in the digital fabric. He noticed that his favorite sandwich chain, Pret a Manger, lacked an iPhone app. In a world he felt was “so much less competitive back then,” this was an opportunity too obvious to ignore.

So he set to work. He went on their website and simply “ripped off all of their IP, all of their logos, trademarks.” He found a way to hack some of their APIs, pulling the menu and other data into a clean interface he built himself. He put it on the App Store, charging what felt like a fair price—99 cents—and watched as it was featured by Apple in the “what’s hot” section. The sales started coming in. For a moment, it was a perfect, self-contained act of creation and commerce, a testament to the leverage a determined teenager could find online.

Of course, the sandwich chain eventually noticed. This was their brand, their menu, their intellectual property, and some random teenager was making money off it. He started getting “all of these angry letters,” the kind written by a general counsel whose job is to eliminate such problems. They invited him to their office, a meeting he assumed was to “threaten me and sue me and all of this stuff.” But when he got there, the corporate armor fell away. They saw not an evil company ripping off their IP, but a “harmless teenager” who had simply built something they hadn’t. In a surprising turn, they decided to make his creation the official Pret iPhone app. The experience taught him a lesson that would calcify into a core principle, a rule for the road ahead. It was, he realized, best to “ask for forgiveness, not for permission.”

“Robot Lawyer” Dorm Room Project goes viral on Reddit

The decision to leave London for California in 2015 was sparked not by a university prospectus, but by a series of YouTube videos. From a room where it was seemingly always raining outside, he had watched Stanford’s online classes, mesmerized by the introductory shot that zoomed down a sun-drenched Palm Drive. The image was “so magical,” a foreign landscape of warmth and possibility. The initial reason he wanted to go, he would later admit, was simply because of the weather. But when he arrived at eighteen to study computer science, he found the reality was a “dream come true” in ways the videos could never capture.

He had left behind a culture where high schools were measured by the number of students they sent to Oxford, where the “biggest pinnacle of success is if you get a PhD.” The United States, and Stanford in particular, felt “so much more entrepreneurial.” It was a night and day difference. The first thing he noticed was that there were “loads of people like me.” He walked into his dorm and saw them everywhere: people working on startups, coding projects, sketching out ideas on whiteboards. It was a world that didn't just tolerate his ambitions but celebrated them, a place where building things was the default language.

He was immersed in the intoxicating startup culture of Silicon Valley, yet he remained tethered to the justice-oriented mission forged in his London home. While many of his peers aimed for jobs at the tech giants that loomed over Palo Alto, he felt a different pull. He had no desire to work at Facebook or Google; he wanted to work on something that “gives justice to people.” Stanford was his father’s alma mater as well, a small historical echo, but his path was his own. By his sophomore year, the personal frustration with bureaucracy that had followed him across the Atlantic was already crystallizing into a legal-tech project. He was in the right place, one that was singularly focused on building and work. He was home.

The company Josh started from his dorm room, was an accident, born from a mundane and relentless frustration. The move to California did not absolve him of his knack for collecting parking tickets; the problem simply followed him from the streets of London to the manicured curbs of Stanford. The appeal process was a labyrinth of bureaucratic language, a repetitive and costly ritual designed to exhaust the citizen into submission. He had gotten a lot of tickets, and he saw a system that could be automated. He was an “act-stands-all entrepreneur,” a builder who loved doing projects and stuff, but he never really saw himself as a founder of a company.

So, in the summer of 2015, using the coding skills he had taught himself, he built a solution. In a single night, between midnight and three in the morning, he coded the first version of a free web chatbot to automatically contest the fines. He built it just for a few friends, a small tool to solve a shared annoyance. Then he put it on Reddit, and it went viral. He had stumbled into something. He thought, “wow, maybe there is something to this idea.” The project, which he called DoNotPay, quickly gained media attention, branded the “world’s first robot lawyer.”

Still, he saw it as a public service, a piece of civic tech. His initial vision was to make it into a “website nonprofit,” a way to level the playing field against impersonal authorities. But the idea had caught the attention of Silicon Valley’s architects. Soon after the viral launch, he found himself at breakfast with Marc Andreessen. He was still in the “London bubble,” a student “fresh off the boat in the UK,” speaking philosophically about nonprofits versus for-profits. Andreessen, a man who had built empires on the internet, offered a different perspective. The biggest impact on the world, he argued, is made by “capitalist for-profit companies.” He then gave Josh two pieces of advice. First, “you can take it slowly,” a caution against the hyper-growth ethos that consumed so many young founders. And second, a promise that transformed the project’s future: “Andreessen Horowitz will be the first pre-seed investor.” In that moment, the accidental project became a company.

Silicon Valley lawyer advice to raise millions.

The early backing from Andreessen Horowitz and the glow of viral press were not a guarantee. The path forward was a hard lesson in the specific grammar of Silicon Valley capital. In his sophomore year at Stanford, he applied for Peter Thiel’s prestigious fellowship program and was rejected; he was told he had “no direction.” The project was hot, CNN was writing articles about them, but he couldn’t translate the buzz into the fuel he needed. By his junior year, the server bills were becoming “very expensive,” and he needed to hire some of his smart friends to keep it all going. He set out to raise a proper seed round.

He walked the length of Sand Hill Road and one after another, the doors closed. He pitched to eighteen or nineteen firms, a long and humbling procession of no’s. It was a “really stressful” period. He was close to dropping out of school because he was at the end of his rope. He was “not knowing what to do.” The project that had initially felt so inevitable was on the verge of becoming just another abandoned idea, and he feared he might have to give up, to join another company or to change direction completely.

With only one or two pitches left, he met a lawyer he had brought on as an advisor, a partner at Wilson Sonsini named Damian Weiss. He was too young for drinks, so they met for coffee. He laid out the problem, the string of rejections. “What am I doing wrong?” he asked. Weiss had him do a mock pitch right there. After listening, the diagnosis was swift: he was doing it “completely wrong.” The advice was a set of three minor changes that would alter everything. First, no one cares about a deck; a pre-seed company needs a product demo. Second, he had to put the logos of huge companies like Intuit and Honey in his slides to show the scale of his ambition. Third, he needed to leave the business model “more open,” to stop being prescriptive and let investors imagine the future for themselves.

He went home and re-architected the pitch overnight. The next day, he walked into his final meeting. The difference was like “night and day.” They didn’t just like it; they invested on the spot. And in the close-knit community of the Valley, that single yes was a signal flare. The floodgates opened. Suddenly, “everyone, even the people who previously rejected me were flooding in.” He had learned that substance wasn’t enough; you had to master the narrative.

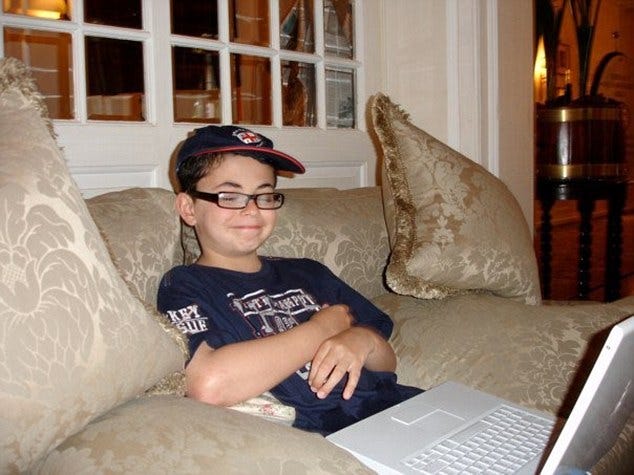

A $10 million IBM campaign.

Two encounters, coming in quick succession, taught him how to operate in a world of giants. The first was a lesson in the strange physics of corporate marketing. In passing, he mentioned to a journalist that DoNotPay used a small piece of IBM’s Watson API to help read parking signs. It was a minor detail, a single technical thread in his larger project. But the comment was picked up by someone on the IBM marketing team, and to them, it was a revelation. It was as if they had been shouting into the void and finally heard an echo. He pictured them thinking, “Wow, someone’s finally using IBM Watson. We finally have one user.” The response was immediate and overwhelming. Days later IBM invested ten million dollars in a nationwide co-marketing campaign. Overnight, he was in Times Square, his project’s name splashed across billboards proclaiming, ‘DoNotPay is powered by Watson.’ It was a surreal lesson in leverage: he learned that aligning yourself with a big company is helpful; the world is a tough place, and “the more allies you have… the better.”

Warren Buffett tells Josh a story he's never told before.

The second encounter was perhaps even more profound. An email arrived, the kind that seems too good to be true, its subject line reading like a fever dream: “Do you want to have lunch and interview Warren Buffett on stage in Seattle?” Josh was still early in his Stanford journey, and he was sure it was a scam, “probably some phishing email.” But he called the number, and it was real. Microsoft was flying a college student out for their annual investor conference, and for some reason, they had picked him. A few weeks later, he was on a plane.

The pressure was immense. He was “really stressed,” consumed by the fear of being forgettable, of asking a question Buffett had heard a thousand times. He did not want to be an “NPC, like a non-player character”; he wanted to be unique. On stage, sitting next to the oracle of Omaha, he defaulted to the only thing that felt truly his own. He introduced himself and shilled his project, then asked, “what is one time that you fought a big company and you fought for your consumer rights?” Buffett, who was likely expecting a question about markets or moats, told a story he had never told before in public: the first lawsuit he was ever involved in. As a young man, long before the days of credit cards, he was a subscriber to Harper’s Magazine. He tried to cancel, but they wouldn’t stop sending invoices. So, he sued them in small claims court, represented himself, and won. The encounter was a direct transmission of purpose, a confirmation from a legend that the fight he was fighting was timeless.

Life's work.

In mid-2018, he formally accepted a bid from the Thiel’s fellowship, a grant that came with a mandate to leave college and build. He was a Stanford senior, but the decision to drop out was less about the money, the $100,000 was nice, but it wasn’t the point, and more about finding a community. For the first time, he was surrounded by nineteen other young people who understood the specific, isolating challenges of his position, who knew what it was like for a twenty-year-old to try and convince a forty-five-year-old engineer to join his cause.

Now a full-time founder, he confronted what he saw as his single biggest mistake. He had started the website in 2015, and for four years, he hadn’t charged a cent. In 2019, he finally implemented a business model, a decision that “supercharged the company.” It gave them a clear, ruthless metric for progress, it tethered their success directly to their customers, a far more honest alignment than the abstract promise of a Facebook-style advertising model. He rejected the prevailing Silicon Valley playbook, the high-burn culture he saw as an “endless Ponzi scheme of hiring,” where capital is raised only to be spent on more engineers who then hire more engineers.

Instead, he embraced the “DoNotPay lifestyle,” a frugal, disciplined approach to growth. He built a machine, not a family. The engine was organic. The company wrote “thousands and thousands of articles and guides on how to fight for your rights,” pieces on how to get an airline refund or dispute a utility bill. These would rank for free on Google, and as frustrated consumers read through them, a simple button would appear every few paragraphs: “Let DoNotPay, do it for me.” And of course, he knew, “everyone’s so lazy, they click the button.” This relentless SEO strategy, combined with the aggressive automation of customer support, allowed a “very small team” to serve hundreds of thousands of users.

The machine was lean and profitable. This efficiency led to a move that was practically unheard of, an act that went “against the system.” He decided to pay a dividend to his employees and investors. He was told by founder friends that a company like Google would never do such a thing. A month later, Google announced its first dividend. It was a moment of profound vindication, a testament to his philosophy that you must remain paranoid and observant, because the world is always changing. He saw that people valued liquidity and profitable businesses, and he had built one that could deliver.

Today, he sees DoNotPay as his life’s work. The company that began as a simple template business has evolved, and now with AI, he feels that “a lot more is possible than previously was.” But alongside this primary mission, a second has emerged: to help the next generation of founders. He is now an interviewer for the Thiel Fellowship and manages his own fund investing in young founders. He believes that these young founders make better investments because “they have everything to lose.” He has seen the alternative play out in real life: give a team of ex-Google engineers five million dollars, and they won’t build the product; they’ll just hire their friends. He would rather back the founder who sleeps two hours a night, who is all in, who will take a fraction of the money and build.

This drive is not just a business thesis; it is the distillation of a family ethos, a “mindset of agency” passed down through generations. He sees it in the story of his grandfather, the son of a communist, who was untouchable in the academic world and had to “scramble to even be a mathematician,” working at a gas station because political prosecution barred him from a military draft exemption. He sees it in his father’s work, passing laws to confront a global superpower. It is the core family belief that “you just really have to push for things he want in the world.” He wants to create more founders because he feels he was in the right place at the right time, and he knows there are thousands of young people stuck in “endless mind-numbing journeys,” waiting for an opportunity.

The relentless push, however, has met with powerful resistance. The “ask for forgiveness, not for permission” philosophy has been tested by the very systems he set out to challenge. In recent years, he has faced multiple lawsuits from prominent class-action lawyers and a government crackdown from the Federal Trade Commission, forcing him to navigate the fraught tension between technological innovation and legal regulation.

Yet his core advice remains unchanged, a direct reflection of his own journey. To the young person learning to code, to the student at Stanford, his message is simple: “please, you should have started yesterday.” He urges them to focus on a problem that is intensely their own. He still, to this day, really hates authority. He is still the type of person who will wait on hold for hours to save twenty dollars. That is the passion he believes in, the kind that can fuel a life’s work. The engine is not the technology; it’s the righteous, personal, and unending fight.